Lahore Fort is located at an eminence in the northwest corner of the Walled City. The citadel is spread over approximately 50 acres and is trapezoidal in form. Although the origin of this fort goes deep into antiquity, the present fortifications were begun by Mughal Emperor Jalaluddin Muhammad Akbar. There is evidence that a mud fort was in existence here in 1021, when Mahmud of Ghazni invaded this area. Akbar demolished the old mud fort and constructed most of the modern fort on the old foundations. The fort's mud construction dates back to the early Hindu period. The fort is mentioned in connection with Muhammad Sam's invasions of Lahore in 1180, 1184, and 1186. It was ruined by the Mongols in 1241, and then rebuilt by Balban in 1267. It was again destroyed by Amir Taimur's army in 1398, to be rebuilt in mud by Sultan Mubarak Shah in 1421, then taken and repaired by Shaikh Ali. The present fort, in brick and solid masonry, was built during Akbar's reign between 1556 and 1605. Every succeeding Mughal emperor, as well as the Sikhs and the British, added a pavilion, palace, or wall to the Lahore Fort, making it the only monument in Pakistan which represents a complete history of Mughal architecture.

There are two huge gates in the fortifications, one each in the middle of the east and the west sides. The western gate, known as Alamgiri Gate, is presently used as the main entrance; however, plans are afoot to open the eastern gate, the Fort's Masjidi Gate, to the general public as well. The Masjidi Gate, built in 1666 during Akbar's reign, was the original entrance to the fort and faces the historic Maryam Zamani Mosque. Alamgiri Gate, a magnificent double-storey gate, was built by Emperor Mohiuddin Aurangezeb Alamgir in 1673 and faces the grand Badshahi Mosque and opens into Hazuri Bagh. The imposing semicircular bastions flanking the gateway have lotus petals at their base and are highly fluted, crowned with small, graceful domed kiosks. The fortification wall is built of small burnt bricks strengthened with semicircular bastions at regular intervals.

For access to the present entrance, from Circular Road (road encircling the Walled City) you should take a turning south, opposite the famous Minar-e-Pakistan tower dominating the expanse of Iqbal Park or Minar-e-Pakistan Park (formerly Minto Park). The wall that you will notice from the Circular Road is the Sikh Period perimeter wall, beyond which the original Mughal fortification wall is visible. The road leads to Hazuri Bagh and Badshahi Mosque. As you enter the Hazuri Bagh perimeter, you will find the massive Alamgiri Gate on your left side. Before entering the Hazuri Bagh, if you turn your attention to the Mughal fortification wall, you will be able to enjoy a spectacular tile-mosaic mural wall, extending to nearly 1500 feet and about 55 feet high. This is the famed Pictured Wall of the Great Mughals, of which the Hathi Pol-the lofty Shahjahani Gateway—is an integral part. This gateway allowed the royal entourage on elephants to enter the citadel, traversing the elephant ramp that terminates at the forecourt of Shah Burj. The Pictured Wall, so labelled by archaeologist Ph. Vogel in his monograph, extends the whole length of the west fortification wall, with belvederes situated in the Shah Burj including the famous Naulakha Pavilion visible from the lower level. The view from below hardly prepares you for the spectacular structures you will find when you enter the Shah Burj quadrangle.

The mural wall turns the corner and continues as the north fortification wall, with several pavilions situated on the top and overlooking the north aspect—this is the area where once the waters of the Ravi washed the foundations of the fortification wall. This is where a promenade with beautifully laid out gardens by the river bank, along with spaces where elephant and other animal fights were held for the amusement of the royal family and the courtiers watching from an eminence. The Pictured Wall is a spectacular display of Mughal court life and is a remarkable mural, the only one of its kind in the world. where most of the northern wall was rendered in tile mosaic (kashi) during Jahangir's reign, part of the north wall, under Shah Burj and the whole of the west wall is the work of Shah Jahan. Interestingly, the same architect, Abdul Karim Mamur Khan, was employed by Jahangir and during the early part of Shah Jahan's reign, a fact which was instrumental in bringing harmony to the two sections. However, if examined carefully, certain differences can be seen between the walls of the two periods.

The citadel is divided into different sections, each creating its own world within its quadrangle, but they are all interconnected for ease of administration of the fort. In the various sections of the citadel you will be able to enjoy the contribution of successive Mughal emperors—at least three of the Great Mughals are represented within the confines of the citadel, namely Akbar, Jahangir and Shah Jahan. The fourth, Emperor Aurangzeb Alamgir, although he built outside the citadel, constructed the impressive Badshahi Mosque and, like the other three left an indelible architectural mark on the cultural map of Lahore.

Maidan Diwan-e-Aam (Garden of Public Audience) located in the south of the citadel, is the earliest and the most important element of Mughal court ceremonial spaces. Its generous dimensions of 730'x460' providing an arena of enormous scale once framed by a perimeter of cloisters, it allowed the pageantry of the Mughal court to be enacted with extraordinary splendor. The cloisters—numbering 114 according to historian al-Badayuni—and dated to Akbar's period, are no longer extant, their foundations alone defining the garden today. Much damage was caused during the Sikh occupancy and Inter-Sikh wars, and after annexation many cloisters were demolished to construct European artillery and infantry barracks when the Mughal fort served as a British cantonment. From the garden you can see the British ceremonial steps lining the southern edge, leading down to the road considerably below its ground level. Although intended as a grand entrance to the fort when the Mughal wall was demolished to make way for the grand steps, this entrance is no longer used.

Diwan-e-Aam dominates the centre of the north periphery of the garden and carries the focus of all activity, with the marble Jharoka or throne gallery projecting from its rear wall. The Diwan-e-Aam is constructed on a raised platform bounded by a stone katehra or railing. The hall measures 187 feet by 60 feet and rises to a height of 34 feet. On the second storey, there are beautiful cusped marble arches at the back of the building, looking down to Jahangir’s Quadrangle. During the reigns of Akbar and Jahangir, the Diwan-e-Aam consisted of a triple canopy of velvet to provide protection from the sun while the floor was covered with rich carpets. However, among the first orders given by Shah Jahan as emperor was the instruction to replace the velvet canopy by a wooden hall. Soon after, however, a sumptuous chihil stun (40-columned hall) was ordered both in Agra and Lahore. While Shah Jahan's Agra Diwan-e-Aam survives, only the Columns and footprint of the one at Lahore are original—the superstructure arches and roof being a British reconstruction.

The takht-jharoka or throne gallery which is located a few feet above the ground and projects into the Diwan-e-Aam is Shahjahani structure, as is the structure in the rear, the Daulat Khana-e-Khass-o-Aam, overlooking the royal residential quad—Jahangir's Quadrangle situated in the north. Today, the takht-jharoka is accessible to all. After climbing a few steps you might like to contemplate the aura of days gone by. In your imagination you could conjure up the scene of the Great Mughal's court. For it is the Diwan-e-Aam, and its garden that became the stage on which the pomp and grandeur of the Mughal Empire was exhibited. The cloisters were decorated with costly shawls and carpets, each of the grandees competing to outdo the one next door, with the garden itself dotted with silver pavilions of the princes and costly tents of the grandees, lined with velvet, damask and taffetas.

In the Diwan-e-Aam, a portion of the original Mughal floor—brick flooring of 'old Lakhauri brick'—is distinguishable from the remaining floor. The original red stone poly-faceted column shafts, and the multifoil arched bases that had supported the original roof have been re-used in the hypostyle. You will notice a great deal of similarity with those used in Akbari architecture when you visit Jahangir's Quadrangle. The comparatively simple faceted concave capitals that you see here were transformed into elaborate stalactite capitals beautifully rendered with inlay etc. when Shah Jahan's Shah Burj was later built.

Daulat Khana-e-Khass-o-Aam is accessed by following the steps to takht-jharoka. It is a building cleverly placed to provide transition from the highly public area of the Diwan-e-Aam to the private residential apartments of the imperial harem. The throne jharoka, overlooking the Diwan-e-Aam in the south, is set above the human height to ensure an elevated position for the emperor. 8'6" in length and projecting 4' from the wall, the elegant and regal jharoka, with its railing of delicate sang-i-murmur (white marble) is roofed over with an elegant sloping chajja and saddle-backed dome. The 4' wide galleries on the two sides of the jharoka, seem to have extended the whole length of the Daulat Khana, acting as a viewing gallery for court proceedings by the imperial female entourage, no doubt seated behind screens. The building dated to the Shahjahani period was much mutilated during later rules. Consisting of a core of vaulted chambers—the central one an elongated octagon opening into an open-fronted aiwan—the Daulat Khana is bordered by an arcaded verandah circumambulating its three sides. It is a largely arcuate structure sporting, from a simple coved roof, shallow domes on squinches in verandah bays to more complex vaults. From the first floor of the building you can enjoy the freshness of the quad on the north, a chahar bagh bounded by royal pavilions— the zenana of Emperor Akbar. Originally there may have been an access staircase to descend into the quad. However, it is no longer extant. Few of the original decorative elements in the building are now extant—indiscriminate Sikh over-painting and British 'military whitewash' having camouflaged most of the Mughal evidence. There is little doubt that at one time all surfaces were profusely ornamented. In spite of the loss of surface decoration, evidence of the sumptuous rendering of structure and surfaces can still be seen. On the north verandah, there are two sets of beautifully sculpted seh-dara (3-bay) ensembles consisting of a combination of white marble double-column shafts, and grey-black stone base and ornamental brackets. They are original Shahjahani elements, as are the marble dadoes (izara) with courtly inlay borders of double black lines and of multi-colored inlaid zigzag (chevron) design.

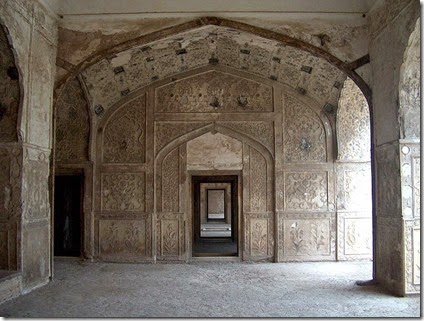

Makatib Khana is located in the northwest corner of the Maidan Diwan-e-Aam. Since there is no access to any quadrangles from the Daulat Khana-e-Khass-o-Aam, you will need to climb down the royal throne steps to return to the Diwan-e-Aam. Makatib Khana is the only inscribed Jahangiri building (1027/1617-18) in the fort, and is well worth a careful examination. It was designed by one of the most accomplished Mughal architects—Abdul Karim titled Mamur Khan, a favourite of both Jahangir and Shah Jahan. Placed ingeniously, this introverted building on the one hand faces the highly public garden (Maidan-e-Diwan-e-Aam) to the east, and on the other provides access to the select quad-precinct of the Moti Mosque located to the north, an area also accessible from several royal apartments located in the northern belt of the citadel. The eastern facade, with its low level arcade, no doubt designed to relate to the height of extinct cloisters bordering the maidan, carries a tall aiwan (portal) in its centre. The inscription above the portal, while ascribing the building's construction to 1027/1617-18, "the twelfth year of Jahangir's accession by the devoted servant Mamur Khan," describes it as "the building of this daulat khana". This structure is conjectured to be part of a group of royal mansions on which the princely sum of seven lakhs Rupees was expended, and which were much acclaimed by Emperor Jahangir in his delightful memoirs. The east arcade facing the maidan incorporates raised platforms likely to have been used as sitting places—indicating their use for news writers, mentioned by the traveler Montserrat as noting down the daily court events. As you step down into 62 ' square internal courtyard, you will find it framed by low-height arcade-like bays on all four sides. The centers of two of these are accented by tall arched recesses and the remaining two by gateways, providing access to east and north mentioned earlier. The arcaded bays employ single-storey, wide pointed arches and accommodate platforms a couple of feet above the courtyard floor, possibly also for the use of scribes. You will find no trace of stone, since Mamur Khan selected the common brick as his basic building material, which once treated with chunam, a polished lime plaster, lent itself to a remarkable array of surface decoration. However, today little of the once dazzling decoration employed as an integral part of the architectural countenance is in evidence. However, a few decorative fragments of colorful fresco based on floral and vegetal themes can still be seen—some in the aiwan ceiling and mucfarnas (stalactite squinches) as well as some in the courtyard alcoves. Makatib Khana leads directly into the Moti Mosque Quadrangle and to the celebrated sang-e-murmur (marble) Moti Masjid, or the Pearl Mosque.

Haveli of Mai Jindan dominates the eastern periphery of the Moti Mosque Quadrangle. Mai Jindan, (Chandan or Chand Kaur), was the mother of the infant Sikh ruler, Dulip Singh. This two-storey building may have originally been a Mughal structure, however, it is considered a Sikh structure due to large-scale additions by the Sikhs. The building now houses a collection known as the Princess Bamba Collection. This is the building where according to Fakir Qamruddin, during the Sikh War of succession the gruesome murder of Rani Jindan took place.

Jahangir's Quadrangle was begun by Akbar and completed by Jahangir in 1618 and contains some of the earliest Mughal structures in the fort. The area is part of a belt of quadrangles and suites lining the northern periphery above the Mughal fortification wall, and was dedicated to strictly imperial usage. Jahangir's Quadrangle, a quad consisting of royal apartments and a harem sera, was placed in a secure corner of the citadel to ensure the safety and security of the zenana. Also, since the river Ravi once flowed at the foot of the north fortification, the view from the royal quads, overlooking the vast countryside beyond, would have been spectacular.

Most of the buildings around this quad are built upon subterranean chambers, particularly those bordering the quad's northern, eastern and western peripheries. From recent studies, it can be inferred that the east and west suites were built at the same time as the subterranean chambers below them, pointing to Akbar as the architect of the imperial chambers.

The iwans represent the best of Akbari architecture in the region that is now Pakistan. In fact in the rendering of the sculpted imagery in the struts, they surpass the elements found anywhere else in the subcontinent. While there are many elements that are evocative of those employed in Agra or Fatehpur Sikri, there is little doubt that as the last capital built by Akbar, Lahore represents the high point of Akbari architecture in view of the experience gained by Akbari architects and crafts persons while building the earlier capitals.

Jahangir's Quadrangle, 372' x 245' in size, is the largest of all quads, except the Maidan Diwan-e-Aam. In the rectangular quadrangle is set a chahar bagh (paradisiacal garden) with parterres and walkways, cooled by an enormous hauz (tank) and an array of fountains. The central chabutra (mahtabi) or platform, accessed by narrow causeways provides a delightful seat elevated above the water reservoir to enjoy the amiable surroundings. A wonderful fairy tale scene setting decorated with oil lamps (diyas) and candles, was witnessed as late as 1843 by the Prussian Von Orlich when he visited the Sikh durbar.

During the British period the suites in the quad were converted into officers' accommodation, and greatly altered with additions made to cater to military requirements. At the time, the vast space of the original roya 1 quad was utilized to build several new structures consisting of 'cook rooms' and school rooms.

Haveli of Kharak Singh, the heir to Ranjit Singh, occupies the southeast corner of Jahangir's Quadrangle. No doubt it was due to its having been utilized by the heir to the Sikh throne that after the British occupation the first floor was considered suitable for the 'Commandant's Quarters', while the ground floor was used as 'godown and servants' house.

The first floor is presently used by the Archaeological Survey offices and ground floor accommodates the Archaeological Library, a remarkable storehouse of antiquarian books. If you have time, it is worth entering the library, since you are allowed to browse through the collection. The whole southern periphery of the quad would also have been lined with suites similar to the porticoes lining the eastern and western edges of the quad. Today, the surviving red stone seh-dara alone provides the clue to the ancient lineage of the structure.

Mashriqi and Maghribi Iwans (East and West Chambers), built by Akbar, define the quad's eastern and western borders. These symmetrically arranged chambers are the most spectacular of the quad buildings. Originally lined with five iwans or suites on each side, each unit is identified by original distinctive features—the red sandstone seh-dara (three-doorway unit) dalan porticoes. The seh-daras carry exquisitely carved columns and the roof chajja is supported by striking sculpted struts composed of the much-acclaimed figures of elephants, griffins and peacocks. Although the seh-dara is a trabeated structure—using beams and struts of stone—the rooms themselves demonstrate arcuate construction techniques in red Lahori brick which were utilized with great effect to produce lofty vaulted spaces and arched apertures.

Some rooms show simple fresco decoration, though in view of the damage inflicted upon these chambers by various rulers, including present-day custodians, it is difficult to distinguish and identify the original elements.

Mashriqi and Maghribi Suites are identical two-storey, detached graceful mansions located at the northeast and northwest corners of Jahangir's Quadrangle. They are of greater height and the east and west chambers and carry greater refinement in the execution of architectural elements. Although they are placed in continuity of the remaining iwans on either side, from their unique character and elaborate ornamentation of structural elements, it is evident that these mansions were reserved for the more illustrious members of the royal household—the queen mother or a favourite empress—or a favourite daughter such as Shah Jahan's eldest Jahan Ara Begam. Surely these mansions were the place where edicts would have been brought to be stamped with the royal seal, which was always in the custody of the most powerful royal lady of the day.

These mansions provide a delightful opportunity, to experience the most exquisite carving of the Akbari period. The polyfaceted, double-storey columns on multifoil bases of the deep set portico, and the moulded and carved brackets supporting the soffit of the deep sloping chajja (overhang or projection), are all incised with a delicate overall pattern. The most stunning of all are the flamboyant, 2-stage highly figurative struts, based on animal imagery, to support the deep eaves.

In each of the mansions, flanking the seh-dara are two projecting semi-octagonal balconies, with their bases elaborately fashioned out of innovative brick corbelling. Faint traces on the muqarnas of these provide evidence of the once highly decorative, embellished and gilded fresco work.

It is worth entering the seh-dara portico of the east suite since you will find an interesting two-level mezzanine arrangement in the portico. From the portico you can view the vaulted rear chambers, and gauge the splendour and loftiness of the accommodation.

Khwabgah-e-Kalan (Bari Khwabgah) is a detached single-storey arcaded palace building located in the centre of the chahar bagh overlooking the north aspect of the fort. Through its rear openings could once be viewed the verdant surroundings bordering the river Ravi. Today, the Ravi, having receded, is no longer visible, while the Bari Khwabgah (Great Chamber of Dreams) is a much disfigured version of the original building attributed to Jahangir.

In view of the evidence of historical sources regarding Jahangir's habit of rebuilding on the foundations of buildings constructed by his father, Emperor Akbar, the Jahangiri palace itself is likely to have been built upon the walls of an earlier palace or khwabgah, below which lie the subterranean chambers attributed to Akbar.

The current building presents a 19th century remodelled veranda in the front, while the 3-chamber arrangement in the rear with thick walls, vaults and squinches is indicative of original construction. During the British occupation of the fort, new constructions totally camouflaged the original structure and for a time, the building was thought to have been constructed by the Sikhs. However, after the removal of various additions, the building was taken in hand and was 'restored'. The pointed arches as part of the reconstruction effort were believed by the 'restorers' to be Jahangiri architectural expression, but really have no affinity with Jahangiri architecture.

You may not be able to view the interior of the building, since it is utilized as a museum and is open during fixed hours only. However, it is worth timing your visit to the fort so that you are able to view the collection. The interior is also worth a visit to examine the original arcuate construction of the chambers, in which evidence of fresco work on qalib kari (stalactites) can also be seen.

Bangla Pavilion is often mentioned as a Sikh structure, it is more likely to have been of Jahangiri origin. Flanking the Khwabgah-e-Kalan were once two 3-chamber structures, carrying bangladar roofs. Only one of the pavilions is now extant. Its echo, the western pavilion having been lost during the 19th century, its location in dotted lines is indicated on maps prepared by H.H. Cole in the late 19th century. In the absence of any recorded evidence, these pavilions could well have been among the 'sitting places' that Jahangir mentions in his memoirs with evident enthusiasm.

The location of these pavilions, in close proximity of the royal Chamber of Dreams, the khwabgah, overlooking the north fortification wall as well as enjoying a view of the chahar bagh of the Quadrangle, confirms their significance as royal apartments. The large hall has a seh-dara arrangement on the south, although the architectural vocabulary is disparate from the seh-daras seen in Akbari iwans. The columns are simple and are similar to the ones noticed earlier in the Makatib Khana east arcade.

The bangladar roof of the pavilion is also worth noticing, since the central unusual roof line is combined with flanking shallow domes. Although most of the decorative features are lost, traces of fresco, mainly consisting of floral themes and human figures influenced by European imagery, will be found that are indicative of Jahangir's artistic preferences.

It is unclear how the pavilion was utilized. Historical sources are silent on the usage of these pavilions. Were they belvederes for enjoying the cool evening breeze, or did Jahangir utilize these as Jharoka-e-Darshan (or Bangla-e-Darshan) as he did at Agra? If Jahangir did build the khwabgah and the two bangla pavilions, it is likely that his famous rassi-e-adal (the chain of justice) consisting of pure gold 30 yards long carrying sixty small bells, would have been attached to the domed kiosk of the adjacent burj (tower). He might well have appeared for darshan (public viewing) in the lost bangla pavilion.

Zenana Hammam occupies the southwest corner of the quad in a highly damaged state. A Sikh-period map identifies it as a bath (hammam). It is likely that this is the hammam that was built for the use of the imperial female entourage of the emperor—the imperial zenana.

Shah Jahan's Quadrangle, located on the left (west) of Jahangir's Quadrangle is a much smaller 150' x 150' square. The quad incorporates a chahar bagh, its four sections divided with walkways and central axis marked by a 31' x 31' marble platform incorporating a water reservoir (hauz). A 19th century account by Ph. Vogel describes a silver gilt pavilion that was placed on the platform. As in the case of many Sikh ornaments and bric-a-brac, the silver pavilion was sold by auction by John Login in 1848 after he took over the fort as governor.

In view of the number of buildings named after Shah Jahan or attributed to him, along with evidence of his favorite building material—white marble—being utilized in buildings as well as in paving and garden platforms, it is evident that this was among the favorite residential areas for the emperor on his visits to Lahore. The marble paving is no longer in place since it was stripped and taken to be utilized in the new church built at Mian Mir during the 1850s.

The quadrangle is bordered by a building known as 'Khwabgah-e-Shahjahani', contiguous to which is the royal hammam, while the northern periphery is dominated by the elegant white marble pavilion known as Diwan-e-Khass.

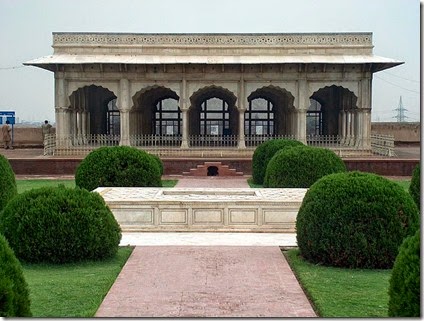

As in the case of the earlier Jahangir's Quadrangle, the northern periphery boasts the most important structure in the quad, an elegant white marble baradari marking the central axis—known as Diwan-e-Khass. This building is sometimes referred to as Chotti Khhwabgah or Khwabgah-e-Khurd (Minor Sleeping Chamber). Although reconstructed due to damage caused to it during the Sikh rule, the baradari probably retains much of its original character.

Diwan-e-Khass, the marble pavilion of exquisite beauty, was in the past referred to as Chotti Khwabgah, also as Khwabgah-e-Khurd (Minor Sleeping Chamber)—the name khwabgah most probably being an appellation given by the Sikhs. The building also did duty as the garrison church during the British occupation of the fort, when the elegant fountain and the marble screens in the north were filled with concrete. At the time a baptismal font was placed in the central alcove, a place which 19th century archaeologist Henry Cole noted, "Shah Jahan would most likely have selected for his couch to catch the air through the marble lattice." The building was reconstructed during the British period restorations, utilizing the original elements, but it is likely that the roof structure was modified during reconstruction.

Most scholars agree that this is the sangi-i-murmur pavilion which Shah Jahan came to inspect in the fort in 1645, since this is the only extant building built entirely of marble (except for the Moti Mosque) which overlooks the river.

With an almost square footprint 52' x 52', there are an equal number of arched bays on all four facades. The north aspect sports massive wall-like piers which form vaulted alcoves, while the remaining portion of the building carries a coved roof supported on classical Mughal columns. Due to its hypostyle character the pavilion has an elegant transparent air.

When the Ravi flowed along the north fortification wall, the cusped arched openings on the north, carrying marble geometric fretwork screens incorporating viewing windows would have provided a delightful prospect.

Also worth examining are the poly faceted columns and stalactite capitals. Also of note is the beautifully crafted scalloped white marble fountain—a neat device to cool the air wafting in through the open pavilion. Its basin hollowed out in the floor of the central bay, though ravaged, still contains vestiges of courtly pietra dura. The flooring is also neatly executed, and the fine black inlay pattern in white marble in the flooring of the two alcoves is a treat. You might also like to notice the fine pietra dura work in the parapet encircling the building.

If it is Shah Jahan's Diwan-e-Khass, this is where the emperor would review the petitions of subehdars (governors) through wakil (an advocate) or wazir (a minister) once they had been processed by the royal prince in charge of correspondence, and before sending them to be stamped by the royal seal. The seal would be in the custody of the emperor's first born Begam Sahib Jahan Ara Begam, his wife Mumtaz Mahal having passed away before this was built.

As you look down from the viewing windows of the Diwan-e-Khass, immediately below you will notice a dilapidated structure, used as a stable during the British Period. This is labeled Arzgah on Sikh period maps, referring to it as a platform from where petitions and complaints were heard in public by the ruler. Although it is likely to be a Mughal Period structure its date is uncertain—its walls having no bond with the fortification wall against which it is constructed, indicating its construction at a later date than the north fortification wall.

It is conjectured that this is the place where the grandees would assemble in the morning to receive the emperor's commands. It is likely that it was constructed as a complementary structure to the Diwan-e-Khass, since it is located immediately below and at the same axis as the former building.

Intizar Gah is located on the northeast corner of Shah Jahan's Quadrangle and is presently used as the Archaeological Rest House. Since a lot of reconstruction took place during 1935-36, it is difficult to date this building. However, it can be asserted with confidence, that at least the eastern portion of this structure belongs to the original iwans bordering Jahangir's Quadrangle.

The reconstruction and additions are an attempt to match the architectural outlook of Shah Jahan's Diwan-e-Khass rather than the Akbari iwans of Jahangir's Quadrangle. The large semi-octagonal structure that you see at the northern end of the western periphery is popularly referred to as 'Lal Burj' (the Scarlet Tower), a Sikh appellation. The eastern periphery of the quadrangle is bordered by the western aiwan of Jahangir's Quadrangle;

Khwabgah-e-Shahjahani is a large building dominating the southern periphery of the quad, and marked as 'marble baradari' on Sikh Period maps. A rather heavy-set building, and not a baradari (baradari= a pavilion with 12 openings), it might have carried marble cladding at one time. Today it is bereft of most decorative features, with just a trace of the marble which might once have beautified the facade. This is not surprising in view of the damage inflicted on it. Vogel's reports indicate that a projecting portico in the centre was "ruthlessly cut off" during the 1850s. The only indication of the extent of the portico today is the slightly raised platform incorporating a finely sculpted marble scalloped fountain.

If it is the khwabgah then it can be inferred from historical sources that it was built in 1634 and was among the first Shahjahani buildings of the fort. Shah Jahan's first visit to Lahore as emperor took place during the seventh regnal year (1634). At this time he reviewed the palace buildings critically from the point of view of his own residence.

A contemporary court historian Muhammad Saleh Kamboh informs us that the emperor turned his attention to the repair of palace buildings, which had been neglected over the years. He also decided to reconstruct the buildings of "the Ghusul Khana (bathroom) and Khwabgah" since the existing palace buildings, probably those dating to Jahangir's period, "were not in reality pleasing to the Imperial mind in their plan and style." It is probably the same building which was entrusted to the Governor of Lahore Wazir Khan, when Shah Jahan was on his way to his sojourn in Kashmir. However, the famed tile-mosaic extensively used by Wazir Khan in some of his other constructions, e.g. the Wazir Khan Mosque or the Shahi Hammam in the Walled City is not in evidence.

The structure is commodious with lofty chambers. Its location on the central axis, and its closeness to the imperial zenana quarters of Jahangir's Quadrangle, is an evidence of its importance as being reserved for royal usage. It could be a khwabgah as the present appellation suggests. On the other hand, the existence of a hammam contiguous to it may point towards its being Daulat Khana-e-Khass. One is impressed by the building's arcuate construction, resulting in lofty interiors, incorporating arches, squinches, vaults and qalibkari muqarnas (stalactite squinches), elements which are expressive of the best of Mughal structural techniques. There has been much tampering with it, however, inflicting great damage to its internal features, and the interior has been largely divested of its decorative features. There are some unfortunate samples of more recent tampering consisting of badly-executed mirror work and incised plaster work, as well as indiscriminate plastering, blocking of walls and earlier Sikh Period paintings, which have together destroyed the original spatial character of this splendid structure. Among its noteworthy elements are the three finely carved marble fretwork screens fitted into the cusped arched openings.

Contiguous to Khwabgah-e-Shahjahni on its west are the remains of the Hammam-e-Badshahi (the imperial hammam), built by Shah Jahan. The hammam, known as the Sheron-Wala Hammam during the Sikh period due to the spouts in the form of lion's heads, is in an extremely damaged condition. This is not surprising since the structure did duty as servants quarters during the British Period.

The research during the late 1920s by Moulvi Zafar Hassan of the Archaeological Survey of India has shown that the royal baths incorporated two different enclaves—the eastern chambers for imperial use and the western for the royal harem. The zenana section is no longer extant since it was demolished to make way for a roadway during the occupation of the fort by British troops.

Although you cannot enter the extant portion of the hammam, its remains show the footprints of an elaborate arrangement. The structure was based on arcuate construction and its several chambers incorporated a reservoir with fountains, a cold room (sard khana), a hot room (garam khana) and dressing rooms in addition to latrines. There were cubicles for changing as well as for furnaces to warm the water in the reservoirs, along with providing hot air for the chambers. Plans are afoot to restore and present the various sections of the hammam to the visitors.

Paien Bagh and Khilwat Khana (Chamber of Seclusion) Quadrangle are in continuation with each other. Most of the structures are now lost, except the two major towers—Lal and Kala Burj—jutting out from the northern periphery wall—which define the eastern and western ends of the courtyard.

The first area that you encounter is known as Paien Bagh or the Zenana Garden where remains of foundations indicate the footprints of now-lost structures.

The northern portion of the court is known as Ahata-e-Khilwat Khana (Quadrangle of the Palace of Seclusion)—denoting a private section. However, during the Sikh Period it was known as the Khilat Khana (the Palace of Robes of Honour) or a public arena where nobles, ambassadors and courtiers congregated during the Sikh reign, giving the court with an opposite function and a divergent appellation. Unfortunately, in the absence of historical accounts or recognizable structures it is difficult to declare with certainty the name of this quadrangle.

Khilwat Khana, a small bangladar pavilion of uncertain origin, lies in the centre of the northern edge of the Paien Bagh. This building, marked as the 'Hall of Perfumes' on Sikh Period maps, is usually referred to as the Khassa Khana. Archaeologist Ph. Vogel conjectured that it was probably a khass khana (khass as opposed to khassa), which would have been enclosed with the cooling device of khass tattis (screens of fragrant matting) during summer. However, if it is the Khassa Khana, it would mean royal palace, which would indicate exclusive use by the imperial family. During the British Period it was part of a house for the commanding officer, when the Mughal Khassa Khana was converted into a bathroom.

Lal and Kala Burj (Scarlet and Black Towers), constructed by the Sikhs, are massive 4-storey structures and are thought to have been used as residential apartments. Both are almost similar, semi-octagonal towers and have attached chambers. The towers were designed incorporating galleries at a high level encircling the projecting semi-octagonal portion, and facilitating a breathtaking view of the surrounding country side.

The large semi-octagonal structure at the northern end of the western periphery is popularly referred to by the Sikh appellation of 'Lal Burj' (the Scarlet Tower). The burj projects out from the adjacent fortification wall and also carries a narrow ambulatory overlooking the northern aspect. There are several elements which conform to the constructional elements of the Makatib Khana such as its simple columns, and its muqarnas vault and fresco decoration, identifying the structure with Jahangir rather than with Shah Jahan. In order to enter the tower you will need to use the opening from the Shah Jahan Quad.

The tower underwent extensive repairs during the mid-1930s when it was found that it was suffering from unequal settlement. At the time its tendency to incline outwards was halted through remedial measures, that is to say, strapping and tying with iron rails. Attached to this residential tower are a few extant chambers, though foundations alone of others are now extant.

The Kala Burj is entered from Shah Burj (Royal Tower) Forecourt. Although normally kept closed, if you can gain permission to enter, Kala Burj is definitely worth a visit. It has been definitively dated to Jahangir's period by the historian Ebba Koch, and represents some of the remarkable imagery of the period. The ceiling of the tower carries a singular rendering of angels and birds, influenced by European art. The tower decoration also portrays Jahangir's fascination with painting, particularly his attempts at encouraging Mughal court artists to paint according to the themes and style of Renaissance painters.

Shah Burj or Royal Tower is the most well documented group of buildings in the Fort. The controversy regarding the authorship of this tower—also referred to as Mussaman Burj (or the octagonal tower) was laid to rest by Moulvi Nur Bakhsh in his writings in 1902-3, when he concluded that the Shah Burj of Shah Jahan mentioned in the inscription on the Hathi Pol Gateway was none other than the Sikh-appellated Mussaman Burj. Hathi Pol is the same impressive gateway that one passed through when the British Period 'postern' gate was being used as the main entrance while Alamgiri Gate was under repairs.

Reception Court occupies the first part of the group of buildings of Shah Burj. Although few chambers with arched alcove frontages are now extant, the once elaborate architectural perimeter of the court can be gauged. The remains of foundations also give an indication of a cloistered space, framed on all sides by chambers and punctured by passages or gateways. From an imagined reconstruction it is evident that an entrance provided convenient access from the Paien Bagh or the zenana garden into Shah Burj's reception court. The reception court was designed in a manner that made it easily accessible on one hand from the imperial zone in the east of the fort and on the other hand from the Hathi Pol situated on the west through a twisted flight of wide steps. The Hathi Pol entry facilitated secluded entry directly into the imperial zone of the fort—the imperial family arriving atop caparisoned elephants.

The court is dominated by the Gor Darwaza, a gateway which leads from the reception court into the Royal Tower Forecourt. The porch-like gateway—a porte cochere—with a simple cusped arch on the south side, incorporates alcoves for sitting comfortably in the shade provided by its vaulted roof. The gateway arch on the north side is lined with white marble. Within the cells bordering the south edge of the court is tucked away a small mosque, presently inaccessible, thought to be for the use of the imperial zenana; however, this could not be established with any certainty.

The eastern periphery of the forecourt is punctuated by the Kala Burj, described earlier. However, the eastern periphery is largely a blank wall today distinguished by three niches framed by cusped arches. Worth inspecting is the central one accented by a carved marble chini khana sawan bhadoon similar to the one found at Shalimar Gardens.

There is hardly any evidence of a structure that might once have dominated the central part of the northern periphery, considering that it must have been a choice location in view of the scenery beyond. Today there is a non descript parapet defining the northern edge.

Ranjit Singh's Athdara is located on the western periphery of the reception court, beyond which is situated the Shah Burj, that today dominates the forecourt. This Athdara—eight doorways as the name implies—was constructed by Ranjit Singh, and used by him as kachahri or court of justice. It is an interesting structure, very much in the Mughal architectural tradition, that was built by the Sikh ruler. Research shows that most elements of the Athdara in fact belonged to the Shah Burj structures which were removed and reused to erect this sumptuous pavilion—an object of interest to 19th century European artists.

Shah Burj (Royal Tower) Quadrangle is accessed by climbing up an undistinguished ramp located on the west next to the Athdara. Walking up the ramp, you arrive in Shah Jahan's sumptuous Shah Burj, more than 6' above the forecourt floor level. As you step into the paved chahar bagh—in contrast to the usual landscaped paradise garden—you have arrived in the midst of the most famous of structures in the Mughal Fort.

From the chronicles it is evident that the original semi-octagonal footprint of the royal tower, jutting out from the face of the north fortification wall, was devised by Jahangir (its octagonal shape leading to the Sikh appellation Mussaman Burj). The foundations and lower portions of the subterranean chambers were constructed in the 19th year of Jahnagir's rule (1624). However, when Shah Jahan became emperor and reviewed the designs—and we know how deeply attached Shah Jahan was to Lahore, having been born and brought up there during the early years of his life—he ordered the raising of the floor level, and this is the reason for its higher floor level compared to that of the adjacent forecourt. It was Yamin-ud-dawla, the trusted noble of Shah Jahan (also his father-in-law) who then laid before the emperor "several plans which the masters like Sinmar had made in consultation with him [Yamin-ud-dawla]."

It was Mamur Khan's designs (the architect who was much favoured by Jahangir), that were selected. This was fortuitous, since Mamur Khan had worked extensively on the Lahore Fort and is likely to have been instrumental in the design and execution of the Pictured Wall. Thus he was able to bring a measure of uniformity and compatibility to the whole complex along with the continuity of the spectacular Pictured Wall—the tile mosaic mural on the fortification wall encircling the northern and western aspect.

While the other quadrangles are designed with the parterres of the chahar bagh, you will find the Shah Burj Quad fully paved. The pattern on the floor of black marble and a variegated marble known as sang-i-Maryam, also referred to as sang-i-abri, is particularly interesting. The paradisiacal imagery is embodied in a perfectly square 131'x131' courtyard, its subdivision attained by the four narrow watercourses. A large water reservoir—an outer square of 54'x54' with an inner circle dominates the centre.

Instead of the natural vegetation found in usual chahar bagh (four-garden style), imagery based on floral themes—guldastas (bouquets), bunches of flowers, flowers in vases—embellishes the facades of surrounding buildings, recreating the imagery of the paradisiacal chahar bagh.

A causeway leads to the central mahtabi or platform which could accommodate only 'two royal seats'—a much scaled down version of the one that is seen in Jahangir's Quadrangle.

The Shah Burj was always considered the most exclusive of the areas due to its importance in conducting business of state and the fact that only a select few were allowed access to it. The Shah Burj was the exclusive preserve of the Mughal emperor and princes of the blood, and even those holding the exalted office of prime minister were allowed entry only on rare occasions.

The Shah Burj was the "favourite abode" of Ranjit Singh, and suffered the greatest impact of the Sikh rule, when the Royal Tower's skyline was "encumbered with a curious medley of structures." Ranjit Singh called it "the palace" and used it to impress his foreign visitors. It is in the Shish Mahal that he constantly displayed his prize possession, the Kohinoor diamond, and arranged "grand entertainments" for his foreign visitors—Alexander Burnes and Sir Henry Fane being among them—when "nautching, drinking and fireworks in the room fitted with small mirrors" would be arranged.

Shish Mahal was the palace where after the annexation of the Punjab by the British, the sovereignty of the Punjab, along with the fabulous Kohinoor diamond, was passed into the hands of the British. As you turn right at the entrance, you are overawed by the spectacular Shish Mahal commanding the north aspect. This is the famed 'Palace of Mirrors', a comparatively recent name given to the building because of the use of "a mosaic of glass inlaid with gypsum" for its decoration. The Shish Mahal is composed of several chambers and projects out in the form of a semi-octagon from the general alignment of the fortification called the Pictured Wall.

The most impressive part of this structure is the central aiwan (hall) which is of handsome proportions rising to two-storey height. Its white marble arcade composed of sculpted shash-hilali (6-crescent) arches, and the cusped profile of engrailed spandrels is outlined with a delicate line of incised marble inlay.

The Shahjahani historian Lahauri refers to its "twelve pillars of marble" each in fact consisting of four sets of double columns and two sets of respond engaged (attached) double columns, employing classical Shahjahani order. The profiled column bases are worth examining, as is their elegant detailing—they represent the best of Shahjahani pietra dura. The aiwan's interior is eulogized by the historian Lahauri in extravagant terms: "From the intermingling of colours in this sky-reaching structure and lofty mansion, spring adorns the cheeks of tulip and the face of the jasmine."

Unfortunately, tawdry dabbling by later rulers and custodians has resulted in the addition of 19th century porcelain blue and pottery shards, the whole overwrought with mirrors and discordant Hindu-mythological frescoes. Ph. Vogel relates how the young Dulip Singh proudly pointed out his own handiwork in the fresco painting. Today it is difficult to distinguish the original Mughal portions of the ceiling in view of the various structural problems and subsequent repairs.

Flanking the white marble aiwan are the 2-storey west and east 'Paradise Halls' constructed in red stone. Although today shorn of plaster, keeping Shah Jahan's preference in mind, it is more than likely that the red stone was covered with the finely rubbed patyali plaster, which would have made the whole facade white. The seh-dara unit (first noticed in Akbar's suites in Jahangir's Quadrangle) defines the frontage, but is executed in an exceedingly refined ensemble by the Shahjahani architect compared to the earlier structure built by Akbar. The internal walls of the ground floor structures were so elaborately treated that Mughal chronicler Lahauri gifted them with the name 'paradise-like halls'.

Today, you will find amateurish fresco decoration on the ground floor walls of the east dalan. The west dalan, is in a better state of preservation and carries gilt markings. In both cases the flat ceilings decorated with wood fretwork in a geometric pattern are well executed. A similar treatment and more elaborate fresco work is noticeable on the first floor of the paradise halls, but they are not open to the general public.

Walking through the lofty cusped archway of the Shish Mahal aiwan you enter the Shish Mahal Tambi Khana in the rear (north)—a belvedere which once provided a spectacular view of the river Ravi. The north aspect of this 'open-fronted summerhouse' sports an echo of the cusped arch framing within its deep alcove an elegant white marble fretwork screen, within which are set three viewing windows, suitably decorated for the viewing pleasure of the imperial entourage. From here could be surveyed the river scenery and gardens beyond, along with animal fights which were a great source of entertainment. You will find the ceiling of the Tambi Khana as decorative as that of the Shish Mahal aiwan.

The two sides of the Tambi Khana to the north are bordered with east and west 'octagonal chambers' each sporting a domed ceiling. It is interesting to note the construction of corner squinches with muqarnas (stalactite) hoods which are also decorated with mirrorwork.

The octagonal chambers on either side provide access to a 'fine hall', each with splayed frontages facing northwest and northeast. These halls, which appear in the form of deep-set alcoves when seen from the north, have finely crafted marble fretwork railings. No doubt these balcony-like halls provided the possibility of enjoying the entertainment below by the nobles accompanying the emperor, who could stand in full view of the general public gathered to watch the elephant fights in the river promenade, directly below the fortification wall of the Shah Burj.

The internal walls as well as ceilings carry florid mirror work and fresco of uncertain origin. The Mughal partiality for water as a cooling device and for controlling the environment is evident from the presence of three shallow basins extant in the central arched bay of the west balcony. These consist of two circles with a central oval hollowed into the floor adjoining the marble handrail.

East and West Dalans, which are placed at right angles to the 'paradise halls' are on the east and west sides of the quadrangle, and are distinguished by the use of seh-dara units similar to those encountered in the paradise halls, and provide an architectural frame to the central Shish Mahal ensemble.

The east dalan is greatly altered with extensive Sikh Period decoration—not surprising since it served as the Sikh ruler Sher Singh's bathing room or hammam.

The internal walls and coved fretwork ceiling of the west dalan located in the north of the quad is profusely decorated with fresco and gilding. The walls camouflaging the seh-dara unit on the west side are a later addition.

Another dalan on the west side is situated to the south of Naulakha Pavilion. It is similarly constructed, though it has gone through some unfortunate and amateur restoration work which has resulted in loss of original evidence. The recent restoration work, done in a hurry to impress the visiting Queen Elizabeth II, is also crude in its handling of decorative features.

Naulakha Pavilion is the only other structure that can claim to rival the celebrated Shish Mahal. Naulakha is probably a Sikh appellation (lit. pavilion costing 9 lakh rupees). This structure is placed at the central axis of the hauz (water reservoir) and is notable for its drooping bangladar roof, and distinctive pietra dura. Although much ravaged and largely robbed of its semi-precious stones in later periods, it is the same pavilion (bangla) of marble that Lahauri describes, "whose mosaics of cornelian coral, and other precious stones," he enthused "excite the emulation of the workshop of Mani" (the Persian artist credited with miraculous power while painting).

Particularly noticeable is the courtly pietra dura in muqarnas capitals (stalactite capitals), abacus and the space between twin-column polyfaceted shafts. The guldasta (bouquet) and other floral compositions carried in the marble pietra dura dadoes and floral-interlacement borders, both externally and internally, reinforce the paradisiacal chahar bagh theme of the courtyard. The central white marble pierced screen on the west aspect, incorporating delicate floral tracery, is an almost exact replica of the one in the Shish Mahal Tambi Khana. Just as the tambi khana was for select royal use, surely the arrangement of similar three viewing windows placed in this fretwork screen points towards similar usage on the west. It is likely that the roof of this bangla was similar to the dazzling 'gilt copper plates' of Agra's Bangla-e-Darshan, a similarly constructed building with bangladar roof.

Although sometimes the Naulakha Pavilion is thought to be the work of Aurangzeb, in view of Moulvi Nur Bakhsh's translation of Lahauri's text it is clear that the pavilion was part of the original Shahjahani ensemble, and in fact the piece de resistance of the Shah Burj.

South Dalans are comparatively simple chambers bordering the southern periphery of the quadrangle. They present a disparate facade compared to the transparent arcaded outlook found in its other structures.

This is not surprising since, even though most of the Shah Burj structures were not greatly affected, the south dalans were put to various functions by the Sikhs and later by the British, along with robbing them of their architectural elements for re-use in the Athdara. The chambers in the central portion were greatly altered in order to house a collection of ancient, mostly Sikh Period weapons.

The only original elements in two corner dalans that can be identified are the seh-daras found in other dalans as well. The central sitting room mentioned by Lahauri is identifiable due to the extant waterfall (chaddar) discharging into a scalloped pond set within the floor, amplifying the quad's chahar bagh paradisiacal image. This particular sitting place provided a wonderful view not only of the hauz, and its mahtabi (its central platform) but from here the impressive facade of the Shish Mahal could also be viewed in its full glory. Although most of the original features are no longer evident, the waterfall's coloured marble inlay in a chevron pattern is a reminder of the imagery and enhancement of play of water that the Mughal builders excelled in.

According to Lahauri there was a 'blessed khwabgah' along with the south dalans, which was so well decorated as to be "a model of the world-exhibiting cup" (the cup made by Kai Khusrau, the King of Persia and which he used to predict future events). That chamber is no longer traceable, but the fact that a royal bedchamber was part of the Shah Burj reinforces its place as among the most significant of all fort structures.

Timeline

Location of Fort within the Walled City of Lahore

It cannot be said with certainty when the Lahore Fort was originally constructed or by whom, since this information is lost to history, possibly forever. However, evidence found in archaeological digs gives strong indications that it was built long before 1025 AD.

1241 AD - Destroyed by Mongols.

1267 AD - Rebuilt by Anushay Mirza Ghiyas ud din Balban.

1398 AD - Destroyed again, by Amir Tamir's army.

1421 AD - Rebuilt in mud by Sultan Mubark Shah Syed.

1432 AD - The fort is occupied by Shaikh Ali of Kabul who makes repairs to the damages inflicted on it by Shaikha Khokhar.

1566 AD - Rebuilt by Mughal emperor Akbar, in solid brick masonry on its earlier foundations. Also perhaps, its area was extended towards the river Ravi, which then and until about 1849 AD, flowed along its fortification on the north. Akbar also built Doulat Khana-e-Khas-o-Am, the famous Jharoka-e-Darshan (Balcony for Royal Appearance), Masjidi Gate etc.

1618 AD - Jehangir adds Doulat Khana-e-Jehangir

1631 AD - Shahjahan builds Shish Mahal (Mirror Palace).

1633 AD - Shahjahan builds Khawabgah (a dream place or sleeping area), Hamam (bath ), Khilwat Khana (retiring room), and Moti Masjid (Pearl Mosque).[7]

1645 AD - Shahjahan builds Diwan-e-Khas (Hall of Special Audience).

1674 AD - Aurangzeb adds the massively fluted Alamgiri Gate.

No comments:

Post a Comment