Persepolis literally meaning "City of Persians" was the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire (ca. 550–330 BC). Persepolis is situated 70 km northeast of city of Shiraz in the Fars Province in Iran. The earliest remains of Persepolis date from around 515 BC. It exemplifies the Achaemenid style of architecture. UNESCO declared the citadel of Persepolis a World Heritage Site in 1979.

Darius made Parsa the new capital of the Persian Empire, instead of Pasargadae, the old capital and burial place of King Cyrus the Great. Because of its remote location in the mountains, however, travel to Parsa was almost impossible during the rainy season of the Persian winter when paths turned to mud and so the city was used mainly in the spring and summer warmer seasons. Administration of the Achaemenian Empire was overseen from Susa, from Babylon or from Ecbatana during the cold seasons and it was most likely for this reason that the Greeks never knew of Parsa until it was sacked and looted by Alexander the Great in 330 BCE (the historian Plutarch claiming that Alexander carried away the treasures of Parsa on the backs of 20,000 mules and 5,000 camels).

Though building began under Darius, the glory of Parsa which Alexander found when he invaded was due mainly to the latter works of Xerxes I and Artaxerxes III, both of whose names have been found (besides that of Darius) inscribed on tablets, over doorways and in hallways throughout the ruins of the city.

The great city of Persepolis was built in terraces up from the river Pulwar to rise on a larger terrace of over 125,000 square feet, partly cut out of the Mountain Kuh-e Rahmet ("the Mountain of Mercy"). To create the level terrace, large depressions were filled with soil and heavy rocks which were then fastened together with metal clips; upon this ground the first palace at Persepolis slowly grew. Around 515 BCE, construction of a broad stairway was begun up to the palace doors. This grand, dual entrance to the palace, known as the Persepolitan stairway, was a masterpiece of symmetry on the western side of the building and the steps were so wide that Persian royalty and those of noble birth could ascend or descend the stairs by horseback, thereby not having to touch the ground with their feet. The top of the stairways led to a small yard in the north-eastern side of the terrace, opposite the Gate of all Nations.

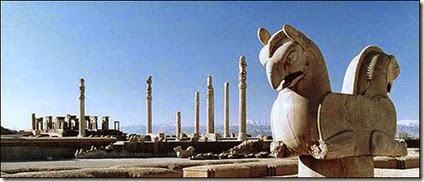

The great palace built by Xerxes I consisted of a grand hall that was eighty-two feet in length, with four large columns, the entrance on the Western Wall. Here the nations which were subject to the Empire gave their tribute to the king. There were two doors, one to the south which opened to the Apadana yard and the other opening onto a winding road to the east. Pivoting devices found on the inner corners of all the doors indicate that they were two-leafed doors, probably made of wood and covered with sheets of ornate metal. Off the Apadana yard, near the Gates of all Nations, was Darius’ great Apadana Hall, where he would receive dignitaries and guests which, by all accounts, was a place of stunning beauty (thirteen of the pillars of the Hall still stand today and remain very impressive).

Limestone was the main building material used in Persepolis. After natural rock had been leveled and the depressions filled in, tunnels for sewage were dug underground through the rock. A large elevated cistern was carved at the eastern foot of the mountain to catch rain water for drinking and bathing.

The terraced plan of the site around the palace walls enabled the Persians to easily defend any section of the front. The ancient historian Diodorus Siculus recorded that Persepolis had three walls with ramparts, all with fortified towers, always manned. The first wall was over seven feet tall, the second, fourteen feet, and the third wall, surrounding all four sides, was thirty feet high. With such fortifications opposing him it is an impressive feat that Alexander the Great managed to overthrow such a city; but overthrow it he did.

Diodorus provides the story of the destruction of Persepolis: “Alexander held games in honor of his victories. He performed costly sacrifices to the gods and entertained his friends bountifully. While they were feasting and the drinking was far advanced, as they began to be drunken, a madness took possession of the minds of the intoxicated guests. At this point one of the women present, Thais by name and Athenian by origin, said that for Alexander it would be the finest of all his feats in Asia if he joined them in a triumphal procession, set fire to the palaces, and permitted women's hands in a minute to extinguish the famed accomplishments of the Persians. This was said to men who were still young and giddy with wine, and so, as would be expected, someone shouted out to form up and to light torches, and urged all to take vengeance for the destruction of the Greek temples [burned by the Persians when they invaded Athens in 480 BCE]. Others took up the cry and said that this was a deed worthy of Alexander alone. When the king had caught fire at their words, all leaped up from their couches and passed the word along to form a victory procession in honor of the god Dionysus. Promptly many torches were gathered. Female musicians were present at the banquet, so the king led them all out to the sound of voices and flutes and pipes, Thais the courtesan leading the whole performance. She was the first, after the king, to hurl her blazing torch into the palace. As the others all did the same, immediately the entire palace area was consumed, so great was the conflagration. It was most remarkable that the impious act of Xerxes, king of the Persians, against the acropolis at Athens should have been repaid in kind after many years by one woman, a citizen of the land which had suffered it, and in sport.”

The fire, which consumed Persepolis so completely that only the columns, stairways and doorways remained of the great palace, also destroyed the great religious works of the Persians written on “prepared cow-skins in gold ink” as well as their works of art. The palace of Xerxes, who had planned and executed the invasion of Greece in 480, received especially brutal treatment in the destruction of the complex. The city lay crushed under the weight of its own ruin (although, for a time, nominally still the capital of the now-defeated Empire) and was lost to time. It became known to residents of the area only as 'the place of the forty columns’(for the still-remaining columns standing among the wreckage) until, in 1618 CE, the site was identified as Persepolis. In 1931 excavations were begun which revealed the glory which had once been Persepolis.

After the fall of the Achaemenid Empire

In 316 BC Persepolis was still the capital of Persia as a province of the great Macedonian Empire . The city must have gradually declined in the course of time - the lower city at the foot of imperial city might have survived for a longer time but the ruins of the Achaemenidae remained as a witness to its ancient glory. It is probable that the principal town of the country, or at least of the district, was always in this neighborhood.

About 200 BC the city Istakhr (properly Estakhr), five kilometers north of Persepolis, was the seat of the local governors. From there the foundations of the second great Persian Empire were laid, and there Istakhr acquired special importance as the center of priestly wisdom and orthodoxy. The Sassanian kings have covered the face of the rocks in this neighborhood, and in part even the Achaemenian ruins, with their sculptures and inscriptions. They must themselves have been built largely there, although never on the same scale of magnificence as their ancient predecessors. The Romans knew as little about Istakhr as the Greeks had known about Persepolis—and this despite the fact that for four hundred years the Sassanians maintained relations, friendly or hostile, with the empire.

At the time of the Arabian conquest, Istakhr offered a desperate resistance. The city was still a place of considerable importance in the first century of Islam, although its greatness was speedily eclipsed by the new metropolis Shiraz. In the 10th century, Istakhr dwindled to insignificance, as may be seen from the descriptions of Istakhri, a native (c. 950), and of Mukaddasi (c. 985). During the following centuries, Istakhr gradually declined, until, as a city, it ceased to exist.

In 1618, García de Silva Figueroa, King Philip III of Spain's ambassador to the court of Shah Abbas, the Safavid Monarch, was the first Western traveler to correctly identify the ruins of Takht-e Jamshid as the location of Persepolis.The Dutch traveler Cornelis de Bruijn visited Persepolis in 1704. He was the first westerner who made drawings of Persepolis. The fruitful region was covered with villages till the frightful devastation in the 18th century; and even now it is, comparatively speaking, well cultivated. The "castle of Istakhr" played a conspicuous part several times during the Muslim period as a strong fortress. It was the middlemost and the highest of the three steep crags which rise from the valley of the Kur, at some distance to the west or northwest of Nakshi Rustam.

French voyagers Eugène Flandin and Pascal Coste are among the first to provide not only a literary review of the structure of Persepolis but also to create some of the best and earliest visual depictions of its structure. In their publications in Paris in 1881 and 1882, titled "Voyages en Perse de MM. Eugene Flanin peintre et Pascal Coste architect" the authors provide some 350 ground breaking illustrations of Persepolis.When years later Pietro della Valle visits Persepolis in 1621 he notices that of the original columns described by Flandin and Coste only 25 of the 72 original columns were standing either due to vandalism or natural processes. French influence and interest in Persia's archeological findings would not end until time of Reza Shah where such distinguished figures as Andrea Goddard helped create Iran's first heritage museum.

No comments:

Post a Comment